I’ve been contemplating writing a cookbook with a title along the lines of “I’m too tired to cook, but why don’t you come over for something simple to eat, anyway,” which should indicate the direction my culinary energies have been headed lately.

I’ve been contemplating writing a cookbook with a title along the lines of “I’m too tired to cook, but why don’t you come over for something simple to eat, anyway,” which should indicate the direction my culinary energies have been headed lately.

So, you can imagine how near the bottom of my list the idea of baking was when I heard that Edible South Shore was holding a baking class last weekend with the magazine’s food editor, Paula Marcoux.

But, Marcoux is one of my heroes for having built her own wood-fired brick oven for about $30 in supplies. (See a previous column) So, even though I didn’t think I wanted to learn any more than I already know about baking bread, I couldn’t resist taking the class because I suspected that Marcoux, being a food historian, would have something special to impart. And she did.

I went to the class ringless, knowing I’d be kneading away, but we never kneaded.

Instead, I learned about a widespread movement in the bread-baking world to make wetter doughs than traditional kneaded doughs. Because the doughs are wetter, they are too sticky to knead, requiring that they be worked differently.

The aim of using less flour – of making wetter doughs — is to produce breads that are airy with big holes inside and have crisp crusts: the kinds of artisanal breads that are becoming more widespread at the marketplace from bakeries like Iggy’s Bread of the World.

“It’s been quite a decade for bread,” said Marcoux, who’s been researching wet dough bread baking since leaving her job as curator at Plimoth Plantation about 18 months ago. Her conversation is sprinkled with references from the work of famous bakers – Lionel Poilane, Raymond Calvel, the authors of obscure 17th century tomes.

And her teaching incorporates so many facts about the variables that affect bread production – enzyme action, steam, surface tension, minimal yeast, lengthy fermentation — that one begins to grasp the complex chemistries that result in the variety of great breads the world over.

Which, surprisingly, isn’t to say that bread baking is difficult or labor-intensive. It’s not, although you do have to know some basic principles and techniques. Nor is it very time-consuming, although it is best done over time – perfect as a background activity during a day at home (longer rising times make much better breads). Still, Marcoux packed a lot of information and baking into a three-hour workshop.

Participants each arrived with a bowl, a wooden spoon, and a tea towel. Marcoux arrived with a vat of yeasty sponge (a watery yeast and flour mixture that is the first stage of yeasted bread making); enough sourdough starter for each of the 10 of us: and a sweet dough ready for forming into cinnamon rolls.

Starting a wet dough is like starting a traditional kneaded dough except that much less flour is used.

Getting the right moisture (hydration) level is thus critical, so Marcoux, like serious bakers everywhere, highly recommends using a simple kitchen scale to weigh ingredients rather than measure them.

“A cup of flour can vary in weight, but four ounces of flour is always four ounces of flour,” she said.

The most essential know-how I got from the workshop was learning two basic techniques that replace kneading in wet doughs.

One is to use a spatula to pull up on the dough in a bowl from beneath it, stroke after stroke, while turning the bowl. Quite easy.

The second main method is to stretch and fold the dough.

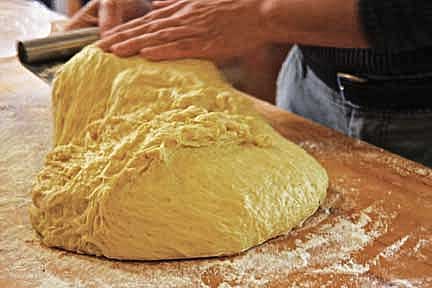

A wet dough is a cohesive mass, quite like a traditional dough, but much less firm. The stretch and fold method allows a baker to work the dough (required for good gluten development) while adding as little additional flour to it as possible.

The technique involves placing the dough on a floured board and sliding a dough scraper underneath it and using the tool to pull and stretch the dough out into a long mass. Once this is done, the tool is used to fold the dough in thirds like you would a letter, which results in a thick square with three layers that can be set aside to rise.

The technique involves placing the dough on a floured board and sliding a dough scraper underneath it and using the tool to pull and stretch the dough out into a long mass. Once this is done, the tool is used to fold the dough in thirds like you would a letter, which results in a thick square with three layers that can be set aside to rise.

What I ultimately took away from the workshop was a renewed attraction to bread baking – drawn by the allure of fermented doughs as living, responsive, almost mystical things.

Seeing them through Marcoux’s eyes and experience inspired me out of my exhaustion. I spent the next day working with the sourdough starter I got from her and baking rolls and sweet rolls.

And they were delicious — better than any I could buy.

I loved that the French style rolls I baked (above), from the dough we made in class, remained fresh for 48 hours and didn’t turn rock-hard like all the other French breads I buy.

I loved that the French style rolls I baked (above), from the dough we made in class, remained fresh for 48 hours and didn’t turn rock-hard like all the other French breads I buy.

And I loved the tangy sourdough boule Marcoux made in class (right) and the fact that it rises in a lined basket. And I love that wet doughs make a lighter bread that can remain lightish even when whole grains are added.

I’m considering a second in my series of cookbooks. It’s not set in stone yet, but the title might be something along the lines of “No-knead baking for somewhat lazy people who love great bread.”

Or, maybe it could just be a chapter in my other book. We’ll see.

Visit Edible South Shore’s blog to find some of Marcoux’s blog entries.

Photographs of dough and boule by Michael Hart; photo of rolls by Joan Wilder